Forgotten Films: Little Fugitive

Mention the name Morris Engle and even the most astute film fan might be reduced to a puzzled stare. Engle was a highly respected photographer but his career as a motion picture director lasted only five years from 1953 to 1958. During this time he produced three features, all of which have lapsed into obscurity. For Lollipops and Lovers and Weddings and Babies, his second and third films respectively, an argument can be made that this could be warranted. Aside from some excellent cinematography and the occasional commitment of history on celluloid, neither film is terribly satisfying or has much to recommend it. His debut film, Little Fugitive, however, seems to have accomplished everything Engle was attempting to cinematically but was apparently lightning that could not be captured in a bottle twice.

Mention the name Morris Engle and even the most astute film fan might be reduced to a puzzled stare. Engle was a highly respected photographer but his career as a motion picture director lasted only five years from 1953 to 1958. During this time he produced three features, all of which have lapsed into obscurity. For Lollipops and Lovers and Weddings and Babies, his second and third films respectively, an argument can be made that this could be warranted. Aside from some excellent cinematography and the occasional commitment of history on celluloid, neither film is terribly satisfying or has much to recommend it. His debut film, Little Fugitive, however, seems to have accomplished everything Engle was attempting to cinematically but was apparently lightning that could not be captured in a bottle twice.

Little Fugitive tells the story of brothers Joey and Lennie Norton. The children of a widowed working mother, the boys are largely left to fend for themselves on some New York streets that are startlingly friendly compared to today. Older brother Lennie has just celebrated his twelfth birthday and one of his presents, in addition to some cash and a harmonica, is permission to go with his friends to the Mecca of northern childhood, Coney Island. Unfortunately, the boy’s grandmother becomes ill and their mother must leave for a weekend to care for her. Lennie, the man of the house by default, is left to care for his seven-year-old brother with just some cash for groceries to get them by until their mother returns.

Little Fugitive tells the story of brothers Joey and Lennie Norton. The children of a widowed working mother, the boys are largely left to fend for themselves on some New York streets that are startlingly friendly compared to today. Older brother Lennie has just celebrated his twelfth birthday and one of his presents, in addition to some cash and a harmonica, is permission to go with his friends to the Mecca of northern childhood, Coney Island. Unfortunately, the boy’s grandmother becomes ill and their mother must leave for a weekend to care for her. Lennie, the man of the house by default, is left to care for his seven-year-old brother with just some cash for groceries to get them by until their mother returns.

Like most siblings, the older Lennie considers Joey a pest and would rather drop him off on a crowded street corner than look after him. He deals with this by subjecting Joey to practical jokes like running off when they are supposed to be playing hide and seek. When Lennie breaks the news to his friends their trip to Coney Island is off because he is stuck at home watching his brother, they come up with a joke that works just a little too well.

With help of a real bolt-action rifle and bullet, the boys convince Joey that he has accidentally shot and killed his brother! As Lennie lies on the ground motionless with a ketchup smear across his chest, Joey bursts into tears and then runs off for home before they can let him in on the gag. After he has had some time to think while hiding in the closet, Joey does what any other seven year old would in 1953 after committing murder; he appropriates the grocery money and heads for Coney Island!

With help of a real bolt-action rifle and bullet, the boys convince Joey that he has accidentally shot and killed his brother! As Lennie lies on the ground motionless with a ketchup smear across his chest, Joey bursts into tears and then runs off for home before they can let him in on the gag. After he has had some time to think while hiding in the closet, Joey does what any other seven year old would in 1953 after committing murder; he appropriates the grocery money and heads for Coney Island!

Early in the film, Joey’s obsession with horses and all things cowboy related is established. In fact, he is seldom seen without his trusty cap firing six shooter throughout the entire film. Once at the amusement park, Joey is overwhelmed by the expansive world filled with carousel horses and pony rides. He spends hours wandering through the Brooklyn based attraction and sampling almost every type of ride, game, and concession it has to offer. While he is still troubled by the occasional pang of guilt, Coney Island contains too many distractions for it to keep him down for very long.

Early in the film, Joey’s obsession with horses and all things cowboy related is established. In fact, he is seldom seen without his trusty cap firing six shooter throughout the entire film. Once at the amusement park, Joey is overwhelmed by the expansive world filled with carousel horses and pony rides. He spends hours wandering through the Brooklyn based attraction and sampling almost every type of ride, game, and concession it has to offer. While he is still troubled by the occasional pang of guilt, Coney Island contains too many distractions for it to keep him down for very long.

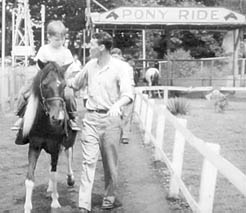

As the day moves on, Joey’s cash flow dries up just as he discovers the pony rides and his first opportunity to experience live horses up close. Dejected by this cruel twist of fate, he visits the free beach area and viewers get an idea of what it was like to be at a crowded northern seaside during the peek season. It is here that the resourceful Joey finds a new source of seemingly endless revenue by collecting discarded glass soda bottles and exchanging them for their deposit value (how’s that for dating this film?).

As the day moves on, Joey’s cash flow dries up just as he discovers the pony rides and his first opportunity to experience live horses up close. Dejected by this cruel twist of fate, he visits the free beach area and viewers get an idea of what it was like to be at a crowded northern seaside during the peek season. It is here that the resourceful Joey finds a new source of seemingly endless revenue by collecting discarded glass soda bottles and exchanging them for their deposit value (how’s that for dating this film?).

The newly flush Joey can now ride the ponies to his heart’s content and bonds with a handler named Jay who has a particular flair for showmanship during the jaunts. This is Joey’s first, and only, extended interaction with an adult in the entire film. Jay finally poses the question of what seven year old boy is doing roaming Coney Island on his own but Joey beats a hasty retreat before he can dig too deep.

After spending a quiet night sleeping on the beach, Joey wakes early and wanders the empty park as the sun rises. He ends up back at his beloved pony rides where Jay, attempting a less direct approach to get to the bottom of this free spirited orphan, offers him a job caring for the horses. Under the guise of getting Joey a social security card from Washington, Jay gathers enough information to track down his home phone number. Instead of a panicking parent on the other end of the line, he encounters a distraught Lennie who begs him to hang on to Joey until he can get there.

After spending a quiet night sleeping on the beach, Joey wakes early and wanders the empty park as the sun rises. He ends up back at his beloved pony rides where Jay, attempting a less direct approach to get to the bottom of this free spirited orphan, offers him a job caring for the horses. Under the guise of getting Joey a social security card from Washington, Jay gathers enough information to track down his home phone number. Instead of a panicking parent on the other end of the line, he encounters a distraught Lennie who begs him to hang on to Joey until he can get there.

As Jay is returning from his clandestine phone call, Joey spies him exchanging greetings with a friendly police officer and once again takes it on the lam. Lennie arrives shortly thereafter only to have his recently restored hope instantly dashed. He explains the situation to Jay who, rather than actually doing anything himself, just tells Lennie to go to the police station. He considers this at first but then realizes the amount of trouble he would be in for if he alerts the authorities and decides to search for Joey on his own instead.

Hours of combing the park bear no fruit for Lennie and he becomes increasingly more distracted by the amusements going on around him. At one point he even abandons his search to spend some time at the beach and play in the surf. As it slowly dawns on him that time is growing short and his mother will be home soon, he spies Joey on the beach just as he is being lifted up on the parachute ride. By the time he reaches the ground again and scrambles to where he last saw him, his brother has slipped away once again.

Tired, dejected, and out of ideas, Lennie is ready to pack it in and face the music when a sudden rainstorm forces him to seek shelter. In addition to delaying Lennie, the cloudburst also clears the beach and much of the park as patrons seek excitement in a drier climate. As the rain subsides and the sun returns, Lennie sees Joey, once again collecting bottles, on the nearly empty sand. The brothers reunite, reconcile, and race off home just in time to arrive before their mother and narrowly avoid punishment. Relieved that her children are safe after their unsupervised weekend (if only she knew!), she promises to take them to Coney Island as a reward! Of course she has yet to discover that neither the money she left nor the groceries she asked for are in the house but the film ends before any little annoyances like that can complicate it.

Tired, dejected, and out of ideas, Lennie is ready to pack it in and face the music when a sudden rainstorm forces him to seek shelter. In addition to delaying Lennie, the cloudburst also clears the beach and much of the park as patrons seek excitement in a drier climate. As the rain subsides and the sun returns, Lennie sees Joey, once again collecting bottles, on the nearly empty sand. The brothers reunite, reconcile, and race off home just in time to arrive before their mother and narrowly avoid punishment. Relieved that her children are safe after their unsupervised weekend (if only she knew!), she promises to take them to Coney Island as a reward! Of course she has yet to discover that neither the money she left nor the groceries she asked for are in the house but the film ends before any little annoyances like that can complicate it.

Taking a page from the Hal Roach Little Rascals film book, Morris Engle is wise enough to turn on his camera and let kids be kids. While shot in 35mm, the majority of it is done with a handheld rig of Engle’s own design that allows him to follow the action fluidly. This gives the film the look of extremely well photographed home movies. The occasional flaw, like an off screen hand steadying Joey on the carousel or a foul ball in the batting cage side swiping the camera, only further adds to the realism.

The story of the Little Fugitive is best seen through the eyes of a child with the appropriate amount of awe and wonder. Due to the absence of adult influences and an underlying distrust of authority, the film can hardly be categorized as appropriate children’s entertainment today, yet it stills plays directly to a child’s fantasies of having unlimited resources and complete freedom. Little Fugitive also shows how far we have come as a society in the last fifty years since no one in their right mind would leave two children this young alone today. Even if they did it would be more difficult and far more dangerous to drop off the grid like Joey does. Viewed with the proper frame of mind and appreciated for the time period it captures, Little Fugitive is still a minor classic of independent cinema.