The Yellow Submarine Chronicles Part Five: They’ll Be Rough Seas Ahead

With a resemblance of a script finally in hand, staff and materials acquired, and individual sequences well underway, it would seem that it should have been smooth sailing for the production crew of the Yellow Submarine but dark skies were on the horizon. A brief period of laborious but fruitful effort did follow in the wake of a written framework finally being distributed but it only lasted a few short weeks for the harried production. As the film began to take shape and a glimpse of the finished product could finally be seen, a rift developed that threatened to sink the Submarine.

With a resemblance of a script finally in hand, staff and materials acquired, and individual sequences well underway, it would seem that it should have been smooth sailing for the production crew of the Yellow Submarine but dark skies were on the horizon. A brief period of laborious but fruitful effort did follow in the wake of a written framework finally being distributed but it only lasted a few short weeks for the harried production. As the film began to take shape and a glimpse of the finished product could finally be seen, a rift developed that threatened to sink the Submarine.

From the onset, there was a distinct division between the artistic and business ends of the project. This was further complicated by the fact that the business end from King Features consisted of an entirely American crew while the artists at TVC Studios were all British. While many small skirmishes had been won and lost between these factions, these were nothing compared to the war that was waged in April of 1968, just three months before the film was due to be released to theaters in England.

From the onset, there was a distinct division between the artistic and business ends of the project. This was further complicated by the fact that the business end from King Features consisted of an entirely American crew while the artists at TVC Studios were all British. While many small skirmishes had been won and lost between these factions, these were nothing compared to the war that was waged in April of 1968, just three months before the film was due to be released to theaters in England.

While accounts very on the order of the events and the formality with which they were conducted, it is a fact that King Features became increasingly concerned that the project was going over budget and would not be completed by the rigid deadline. This culminated in a letter to line producer John Coats from King Features stating that the weekly payments TVC Studios counted on to make payroll were being suspended. The animators viewed this as an attempted takeover of their studio while the business people saw it as a logical penalty for a contractor who was not meeting the terms of their agreement. Whether King Features intended this maneuver to be hostile or not has been lost to time. Al Brodax claims it was nothing of the sort and that there was not anything for King Features to “takeover” on a project they already owned, but the move turned out to be an unwise one.

While accounts very on the order of the events and the formality with which they were conducted, it is a fact that King Features became increasingly concerned that the project was going over budget and would not be completed by the rigid deadline. This culminated in a letter to line producer John Coats from King Features stating that the weekly payments TVC Studios counted on to make payroll were being suspended. The animators viewed this as an attempted takeover of their studio while the business people saw it as a logical penalty for a contractor who was not meeting the terms of their agreement. Whether King Features intended this maneuver to be hostile or not has been lost to time. Al Brodax claims it was nothing of the sort and that there was not anything for King Features to “takeover” on a project they already owned, but the move turned out to be an unwise one.

Had TVC Studios decided to halt production and seek litigation against King Features, the dispute would have spent several years in court and the film would likely never have been completed. King Features could have contracted with another group or groups of animators, but the material that was already completed would have been tied up in the court case and unusable at that point. TVC’s immediate response was to involve the English Trade Union and their legal representatives in the case to impress their position. This caused a temporary standstill for work in the studio as King Features scrambled to review their options. While the lawyers traded phone calls and letters, the animators decided to take more drastic action to insure that their version of the Yellow Submarine did not sail without them.

Had TVC Studios decided to halt production and seek litigation against King Features, the dispute would have spent several years in court and the film would likely never have been completed. King Features could have contracted with another group or groups of animators, but the material that was already completed would have been tied up in the court case and unusable at that point. TVC’s immediate response was to involve the English Trade Union and their legal representatives in the case to impress their position. This caused a temporary standstill for work in the studio as King Features scrambled to review their options. While the lawyers traded phone calls and letters, the animators decided to take more drastic action to insure that their version of the Yellow Submarine did not sail without them.

Over a period of two nights, John Coats, director George Dunning, and a few assistants removed two cans of negatives from Rank laboratories and the corresponding artwork from the studio. This material, which was still considered the property of TVC Studios, represented all the work that had been completed to date and roughly one third of the entire feature film. If King Features decided to continue without the involvement of TVC, they would now be forced to start from scratch to do it. Dunning then locked everything in the basement of his country home until the dust settled on the dispute.

Over a period of two nights, John Coats, director George Dunning, and a few assistants removed two cans of negatives from Rank laboratories and the corresponding artwork from the studio. This material, which was still considered the property of TVC Studios, represented all the work that had been completed to date and roughly one third of the entire feature film. If King Features decided to continue without the involvement of TVC, they would now be forced to start from scratch to do it. Dunning then locked everything in the basement of his country home until the dust settled on the dispute.

Realizing they had no option that would allow them to meet the release deadline without TVC’s participation, King Features backed down in short order and the animation studio regained control of the film. While production returned to normal, King Features was adamant about all remaining work being brought in on budget with no additional funds being forthcoming. At the final tally, TVC went roughly $50,000 over the $1,000,000 budget but this was paid out their pockets in a move that almost bankrupt the already struggling studio.

Realizing they had no option that would allow them to meet the release deadline without TVC’s participation, King Features backed down in short order and the animation studio regained control of the film. While production returned to normal, King Features was adamant about all remaining work being brought in on budget with no additional funds being forthcoming. At the final tally, TVC went roughly $50,000 over the $1,000,000 budget but this was paid out their pockets in a move that almost bankrupt the already struggling studio.

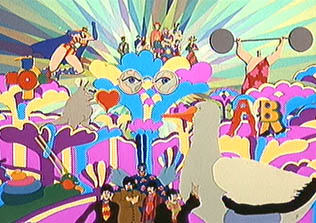

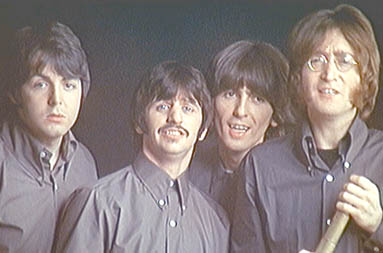

Yellow Submarine was completed on time and reasonably on budget but the constraints are evident in the final product. Lines of dialog often refer to scenes that were underemphasized or omitted entirely, many sequences are more static than intended, and the finale’ showing the Beatles’ live appearance in a fantasy setting was reduced to just the source film of them wearing dark shirts on a drab set. The segment that was impacted the most from these restrictions was the film’s climax. What should have been a satisfying wrap up for the ninety minutes that proceeded it ends up being a hastily tacked on montage of limited animation to the tune of George Harrison’s It’s All Too Much (actually it’s a little too little). This segues into the previously mentioned live action footage, a sequence that was originally conceived as a piece so amazing it would trump all the impressive segments that lead up to it.

Yellow Submarine was completed on time and reasonably on budget but the constraints are evident in the final product. Lines of dialog often refer to scenes that were underemphasized or omitted entirely, many sequences are more static than intended, and the finale’ showing the Beatles’ live appearance in a fantasy setting was reduced to just the source film of them wearing dark shirts on a drab set. The segment that was impacted the most from these restrictions was the film’s climax. What should have been a satisfying wrap up for the ninety minutes that proceeded it ends up being a hastily tacked on montage of limited animation to the tune of George Harrison’s It’s All Too Much (actually it’s a little too little). This segues into the previously mentioned live action footage, a sequence that was originally conceived as a piece so amazing it would trump all the impressive segments that lead up to it.

Given the fact that this was the first feature film of a studio that specialized in producing shorts, they were given a deadline no major animation company would commit to, and the script wasn’t even available until the production was past the half way mark, it is a miracle that this film exists in any completed form. With the negative delivered to King Features, TVC Studios could finally breathe a sigh of relief. The film was finished but it was now in the hands of the distributors and about to be unleashed on the general public.

Given the fact that this was the first feature film of a studio that specialized in producing shorts, they were given a deadline no major animation company would commit to, and the script wasn’t even available until the production was past the half way mark, it is a miracle that this film exists in any completed form. With the negative delivered to King Features, TVC Studios could finally breathe a sigh of relief. The film was finished but it was now in the hands of the distributors and about to be unleashed on the general public.