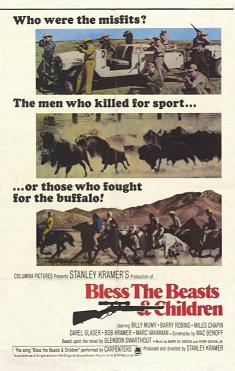

Forgotten Films: Bless the Beasts & Children

Ding (ding) n. – something that don’t fit any where, any time, any thing, any place. It uses up space but it’s useless. Nobody wants it or knows what to do with it, so it’s got no use for livin’.

Ding (ding) n. – something that don’t fit any where, any time, any thing, any place. It uses up space but it’s useless. Nobody wants it or knows what to do with it, so it’s got no use for livin’.

– Wheaties, Box Canyon Counselor, Cabin Four – “The Bedwetters”

Stanley Kramer’s 1971 film was an adaptation of Glendon Swarthout’s (The Shootist) novel of the same name published one year earlier. The book, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, told the story of six misfit youths who are sent to an Arizona boy’s camp, presumably to overcome their inadequacies and become men. Deemed, “emotionally disturbed” by the camp directors, the boys end up in the same cabin together with a counselor who probably has no business around children to begin with. The misfits band together against a society that has cast them aside and embark on a self imposed mission to free a group of buffalo they recognize as kindred spirits.

The Characters:

John Cotton – the victim of a broken marriage between a career military father he idolizes and a social climbing mother who views him more as a hindrance than a son. Cotton is plagued by fits of uncontrollable rage but still rises to become the self proclaimed leader of this band of outcasts.

Lawrence Teft – a juvenile delinquent with a hatred of the authority his successful investment broker father represents. Teft is shrewd and resourceful when the results suit his purpose.

Sammy Shecker – the overweight son of a popular Jewish comedian who lives in his father’s shadow while trying to follow in his footsteps. Shecker is outgoing and loyal to the only group left that will tolerate him.

Gerald Goodenow – a slight and effeminate boy raised from a young age by a widowed mother. Perhaps the most unbalanced of the entire group but his traumas have manifested in non-hostile ways that draw less attention.

Stephen & Billy Lally – two brothers from a wealthy family whose parents care more about social standing than raising children. Billy, the younger brother, is emotionally withdrawn while Stephen blames most of his problems on the unfair attention he believes is lavished on his brother.

Bless the Beasts and the Children begins with the six outcasts starting off on their mission to free a herd of buffalo that have been rounded up for a controlled kill. As the boys sneak out of camp in the dark of night and travel to the hunting site a few towns over, the trails and tribulations that brought them to this point, both personal and as a group, are revealed in flashbacks. While the story is told in a nonlinear fashion, director Kramer uses clever editing techniques coupled with brutal stock footage of a real buffalo kill to tie everything together.

Bless the Beasts and the Children begins with the six outcasts starting off on their mission to free a herd of buffalo that have been rounded up for a controlled kill. As the boys sneak out of camp in the dark of night and travel to the hunting site a few towns over, the trails and tribulations that brought them to this point, both personal and as a group, are revealed in flashbacks. While the story is told in a nonlinear fashion, director Kramer uses clever editing techniques coupled with brutal stock footage of a real buffalo kill to tie everything together.

Box Canyon Boys Camp is the type of rugged outdoors environment that six kids from the city would feel completely lost in even if they weren’t already dealing with a basket full of emotional issues. The cabin arrangements are not assigned so that the boys can segregate into groups of their own choosing and, of course, this means the rejects all end up together after a few weeks. The cabin names are a designation of social standing that can be won or lost based on athletic and artistic achievement and even cunning if one cabin successfully steals the mascot of another. The mascots are the taxidermy heads of various animals with the buffalo, ironically, representing the highest order. Failing at every turn, the misfits of cabin four end up at the bottom of the heap and are given an old fashioned chamber pot and the nickname of “The Bedwetters” to supposedly encourage improvement.

Several weeks into the camp, it becomes apparent that the boys are unlikely to succeed at anything and the directors and counselors effectively leave them on their own. In one last attempt at bonding and perhaps motivating the group, their counselor, Wheaties, takes them on a special field trip. Neglecting to mention that he has won one of the shooting permits by lottery, Wheaties brings the boys to a nearby livestock pen where old and sickly buffalo have been rounded up for a controlled slaughter. The Bedwetters instantly see themselves in a similar situation to these buffalo and make a pact to save them.

Several weeks into the camp, it becomes apparent that the boys are unlikely to succeed at anything and the directors and counselors effectively leave them on their own. In one last attempt at bonding and perhaps motivating the group, their counselor, Wheaties, takes them on a special field trip. Neglecting to mention that he has won one of the shooting permits by lottery, Wheaties brings the boys to a nearby livestock pen where old and sickly buffalo have been rounded up for a controlled slaughter. The Bedwetters instantly see themselves in a similar situation to these buffalo and make a pact to save them.

Liberating horses from the camp, the boys ride them to the highway and then walk into the next town. There, thanks to Teft’s shady skills, they hotwire an old exterminator truck and continue on their way. After stopping for lunch in another town, they attract the attention of a pair of local slackers who corner them outside town and attempt to harass them. Teft once again comes through with a .22 rifle he brought along and sends the cow punks off on foot after shooting one of their tires.

As the journey continues, it becomes apparent through the flashbacks that each of the boys is fighting a losing battle with his own demons. It is only through meeting the other misfits and helping them with their own problems that they have begun to overcome their own. The futile mission to save the buffalo is something they would have never dreamed of individually and would certainly have never made it this far without being able to rely on each other.

As the journey continues, it becomes apparent through the flashbacks that each of the boys is fighting a losing battle with his own demons. It is only through meeting the other misfits and helping them with their own problems that they have begun to overcome their own. The futile mission to save the buffalo is something they would have never dreamed of individually and would certainly have never made it this far without being able to rely on each other.

The boys finally reach the pen at the end of the day and this is where they real tests begin. They arrive on foot after their truck runs out of gas and are faced with a gate lock even Teft can’t pick. After bickering through most of the night and threatening to backslide on the tenacious progress they have made, Teft finally manages to hotwire another truck and they use it to pull the chain off the gate. By throwing their transistor radios set on full volume into the herd and causing as much ruckus as they can muster, they manage to stampede the buffalo but, being the dings that they are, the animals stop only a few hundred yards away to graze. The morning sun begins to rise and the sound of the hunters trucks can be heard in the distance.

Failing to catch the buffalo’s attention with a few well placed shots over their heads, Teft buys the group a few more fleeting minutes by firing his remaining bullets at the rapidly approaching hunters. Refusing to accept failure as an option with their mission this close to success, Cotton dives in the truck and charges the buffalo. His final exchange with Teft as he fights to control his rage is poignant as his friend lets him go, knowing it is his turn to confront his demons. Cotton does indeed succeed at scattering the herd across the plains but at a tragic price.

Failing to catch the buffalo’s attention with a few well placed shots over their heads, Teft buys the group a few more fleeting minutes by firing his remaining bullets at the rapidly approaching hunters. Refusing to accept failure as an option with their mission this close to success, Cotton dives in the truck and charges the buffalo. His final exchange with Teft as he fights to control his rage is poignant as his friend lets him go, knowing it is his turn to confront his demons. Cotton does indeed succeed at scattering the herd across the plains but at a tragic price.

Kramer’s film follows Glendon Swarthout’s book very closely except for the ending. Both end on the same downbeat note but Swarthout chose a more sublime method rooted in youthful foolhardiness. Kramer went with a more topical approach drawing parallels between the Vietnam War that was currently underway. This may tend to date the film slightly but it makes the ending no less tragic. The final scene as the remaining misfits silently stare down the shocked hunters is a chilling classic.

Bless the Beasts and Children features one of the finest youth casts ever assembled for a film. Bill Mumy gets top billing as the talented Teft and turns in a performance about as far removed from Will Robinson of the Lost in Space television series as you can get. I am sure more than a few audience members were surprised by his grim portrayal of a disenfranchised youth on the short track to a life of crime and incarceration. As excellent as Mumy’s performance is, the real star of the film is Barry Robins as the manic Cotton. Robins displays an incredible range playing a character who is the most outwardly normal of the group. During his fits of almost uncontrollable rage, Robins’ facial expressions alone are enough to stir emotion and his final act of sacrifice is truly touching. Sadly this was Robins’ only theatrical role; the rest of his career was inexplicably confined to television and theater until his untimely death in 1986 at the age of only 41. The remainder of the young cast turns in excellent performances that manage to not be overshadowed by the two leads. Surprisingly, only Miles Chapin who plays Shrecker (and years later turned in an almost unrecognizable performance in Tobe Hooper’s underrated film Funhouse) and Marc Vahanian who plays Billy Lally went on to sustained careers in acting. The adult roles are mainly filled by unknowns with the exception of comedian Dave Ketchum as the camp director and supporting actor Jesse White as Shecker’s father.

Bless the Beasts and Children features one of the finest youth casts ever assembled for a film. Bill Mumy gets top billing as the talented Teft and turns in a performance about as far removed from Will Robinson of the Lost in Space television series as you can get. I am sure more than a few audience members were surprised by his grim portrayal of a disenfranchised youth on the short track to a life of crime and incarceration. As excellent as Mumy’s performance is, the real star of the film is Barry Robins as the manic Cotton. Robins displays an incredible range playing a character who is the most outwardly normal of the group. During his fits of almost uncontrollable rage, Robins’ facial expressions alone are enough to stir emotion and his final act of sacrifice is truly touching. Sadly this was Robins’ only theatrical role; the rest of his career was inexplicably confined to television and theater until his untimely death in 1986 at the age of only 41. The remainder of the young cast turns in excellent performances that manage to not be overshadowed by the two leads. Surprisingly, only Miles Chapin who plays Shrecker (and years later turned in an almost unrecognizable performance in Tobe Hooper’s underrated film Funhouse) and Marc Vahanian who plays Billy Lally went on to sustained careers in acting. The adult roles are mainly filled by unknowns with the exception of comedian Dave Ketchum as the camp director and supporting actor Jesse White as Shecker’s father.

The soundtrack to the film also deserves a mention. The title track was contributed by The Carpenters and compliments the film perfectly with its haunting melody and pleading lyrics. The remaining tracks are mostly instrumentals with similarly melancholy tunes. The stand out among these is a beautiful piece called Cotton’s Dream by Barry De Vorzon. Several years after the film’s release, De Vorzon would rework this tune slightly and re-title it Nadia’s Theme. Since 1973, this has served as the theme music to the popular daytime soap opera The Young and the Restless.

Bless the Beasts and Children was a staple on television for many years following its theatrical release but it was almost always presented in a truncated form that eliminated much of the ordeal the boys were put through at camp and some of the more violent footage of the buffalo kills. It received only a very limited home video release from Columbia Tristar on VHS cassette and has never had a legal DVD release in the United States. While the film is probably too strong for younger children, anyone who has ever felt like an outcast or had to overcome adversity just to reach the status quo can relate and appreciate its story.